Coaching on Zoom, “fake” documents to secure a visa and “don’t panic” advice during questions at immigration – this is the story of one family’s attempt to get to the UK.

Sky News follows the journey of a family who came from India on student and dependent visas – obtained they say from “agents” using false documents – but have now spent two years waiting for a decision on their leave to remain.

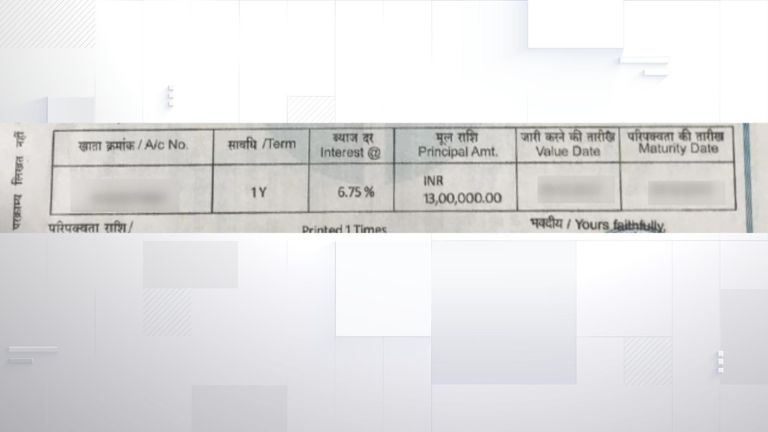

“110% fake,” says Sami. “The agent put the money in the account – which is fake. It’s nothing. But he creates the document like I have the money.”

Sami – not his real name – is explaining how he came to the UK with his wife and two young children on student and dependent visas which he says were obtained by agents – or criminal gangs – in India using fake bank statements.

It is a rare insight into claims of abuse of Britain’s immigration system.

Be in the audience for our immigration debate.

How they got here

Sami says the family needed to show they could support themselves financially in the UK – which they couldn’t.

He says the agents created fake bank documents purporting to show the family had a lump sum of £10,000 in one bank account and a loan of nearly £25,000 in a second account – to cover living expenses in the UK. None of this was true.

He says he paid agents in India nearly all his life savings – more than £20,000 – to arrange a place on a master’s course for his wife.

“I sell my house, then secondly I sell my motorbike – Yamaha – thirdly I sell my wife’s whole gold – earrings, the chain, and some rings,” Sami tells us.

They arrived in early 2023 but when his wife failed to attend the university, they were sent a letter by the Home Office telling them their visas had been cancelled, and they would have to leave the UK by October that year.

Since then, they have been in a cycle of rejections and reapplying for leave to remain, and their case remains unresolved.

A poor man from India, Sami says it was always his dream to live in the UK. So he began researching how to get here.

“UK is my dream country. So that’s why I was choosing the UK. Cricket – Ashes, like England and Australia. My favourite cricketer and bowler, Andrew Flintoff. Greenery, lots of people moving in London. London, then, I decided this is a good place to move.”

Training sessions

When they found the agents to arrange their passage to Britain, Sami says his wife was even given coaching via Zoom while still in India ahead of any potentially difficult questions by UK immigration officials at Heathrow.

In the videos, Sami’s wife repeats her lines again and again.

“Why UK?” asks the woman doing the training. “UK is a multicultural country,” says Sami’s wife.

At another coaching session – this time in the agent’s office, and filmed by Sami – she rehearses: “My hobbies are gardening, reading, newspaper, cooking, baking etc.”

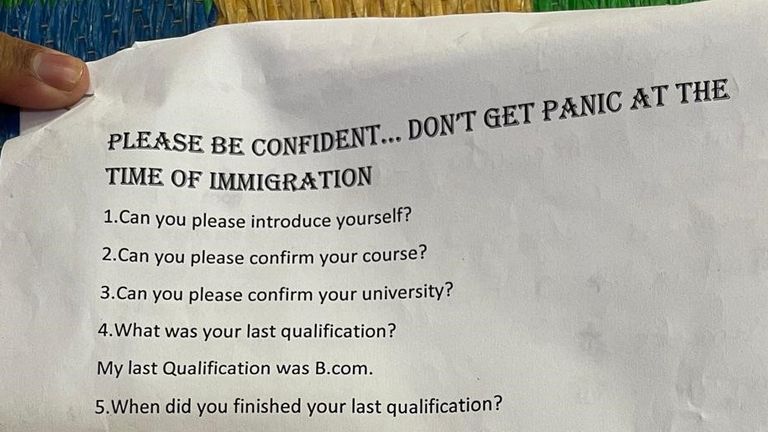

The agents – or criminal gangs – also provided a crib sheet of written tips titled “don’t get panic at the time of immigration”. It contains handwritten notes suggesting things to say about university courses.

But having been granted visas to come to the UK, Sami admits it was never their intention that his wife would study.

Ever since our first meeting, Sami has always clung on to the hope that with two young children – one needing medical treatment – the Home Office is unlikely to send them back to India.

“There is a condition that if your kids are with you, they are not going to detain or deport you. Maybe they give you a chance,” he says.

“My application is still in the Home Office. The government will decide.”

Sami says he is happy they came to the UK – but when we first met four months ago, he and his family were living in one room in a house shared by 13 people.

He isn’t sure of the exact number of people living in the house – or their legal status – but signals: “Upstairs – the bachelors.”

Sami’s wife is cooking in what is basically a cupboard.

“This is a small single room,” he says. “I sleep on the floor, My daughter, and my son, they sleep on the bed.”

Relying on food banks

Subsequently, social services became involved in their case – declaring them destitute because of their immigration status and have provided them with new accommodation.

Sami has been using a food bank run by Asma Haq of the Marks Gate Relief Project.

She says: “As far as they’re concerned they haven’t done anything wrong. But the reality only hits them when they are left penniless.

“They have no accommodation, they don’t know where to go, and the agent stops making contact with them. That’s when they come to food banks like ourselves.”

‘There needs to be a tightened leash’

But Asma tells us she believes Sami is not an isolated case – she believes one in 10 of the people who use the food bank have come to the country illegally or have over-stayed legal visas.

“I just feel like the Home Office’s policies have been quite relaxed and there needs to be a tightened leash. It’s just visas that have been given left, right and centre so easily and so quickly,” she says.

“And the follow-up on the people who have entered into the country on those visas has been poor. Sometimes – I know because I deal with clients – some of them, as far as the Home Office is concerned, they’ve arrived legally.

“But then the paperwork they’ve supplied to the Home Office is actually fake paperwork, fake documentation that they’ve got processed back home.”

A Home Office spokesperson said: “Since we have not been supplied with any identifying information in relation to this case, we are not in a position to comment on the claims made.

“However, stringent systems are in place to identify and prevent fraudulent student visa applications, and we will continue to take tough action against companies and agents who are seeking to abuse, exploit or defraud international students.”