As Boris Johnson jetted off to Saudi Arabia in an attempt to persuade the Kingdom to pump more crude, a reminder arrived that whatever the prime minister’s efforts may yield, it may not be enough to save the world from an oil shock.

The International Energy Agency, the multinational body set up in the wake of the 1973 oil shock, warned in its latest monthly report that energy markets are “faced with what could turn into the biggest supply crisis in decades”.

The IEA expects that, as a result of higher commodity prices and the sanctions slapped on Russia, global economic growth will be slower than expected this year – a conclusion that other forecasters have also reached in recent days.

Latest updates on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

Accordingly, it expects oil demand from April onwards will be 1.3 million barrels per day less than previously forecast.

Today daily demand is now expected to come in at 99.7 million barrels per day for the year as a whole – up 2.1 million barrels per day on 2021.

Unfortunately, it expects oil supplies to fall by more, reflecting the potential loss to the market of up to three million barrels per day from Russia from April onwards.

In other words, while demand for oil is set to fall, supplies of oil are set to fall by more.

As the IEA puts it: “The prospect of large-scale disruptions to Russian oil production is threatening to create a global oil supply shock. We estimate that from April, three million barrels per day of Russian oil output could be shut in as sanctions take hold and buyers shun exports.

“OPEC+ is, for now, sticking to its agreement to increase supply by modest monthly amounts. Only Saudi Arabia and the UAE hold substantial spare capacity that could immediately help to offset a Russian shortfall.”

This explains why Mr Johnson has taken off to Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi.

However, even if both the Saudis and the UAE increase production, there is no guarantee that this would be enough to make up for lost Russian supplies.

The cartel of oil producing nations is, at present, committed to only increasing production by 400,000 barrels per day as it unwinds the production cuts it put in place during the pandemic when demand for crude collapsed and the oil price sank.

This is not just due to what the IEA described today as “Saudi Arabia and the UAE…so far showing no willingness to tap into their reserves”, although that is a key factor, since the pair, along with some other existing OPEC members, have no desire to fall out with Russia – with whom they have been in an alliance, called OPEC+, for the last six years.

The IEA also notes that, even if the Saudis and the UAE were prepared to pump extra crude above the current production targets, it could take between four to eight weeks to reach the market.

Another factor is that a lack of investment and poor infrastructure in some OPEC member countries mean that they are struggling to meet even existing supply targets. The IEA pointed out today that the target is currently being missed by 1.1 million barrels per day.

Adding to the awkward situation is that global crude stocks were already at relatively low levels.

As the IEA notes: “In the absence of a faster ramp up in production, oil stocks will have to balance the market in the coming months.

“But even before the conflict Russia’s attacks on Ukraine, the industry’s oil inventories were depleting rapidly.

“At the end of January, OECD inventories were 335 million barrels below their five-year average and at eight-year lows.

“IEA emergency stocks will provide a welcome buffer, and member countries stand ready to release more oil from strategic reserves if and when needed, in addition to the 62.7 million barrels of crude and products already pledged.”

Industry analysts such as Amrita Sen, of the research consultancy Energy Aspects, warn that these relatively low levels are likely to become more critical when seasonal demand for oil and refined products increases.

The industry usually refers to this period as the US ‘driving season’ – when demand for gasoline (petrol) and diesel increases significantly. Driving season is roughly defined as being the period between the US holidays of Memorial Day and Labor Day which, this year, respectively fall on 30 May and 5 September.

So where might salvation come from?

One possible source is Iran, which is why the US has been anxious to try to revive the 2015 nuclear accord, under which the Islamic Republic agreed to rein in its nuclear ambitions in return for an easing of western sanctions.

The accord, signed by the US, China, Russia, France, Germany and the UK, was scuppered when, in 2018, Donald Trump pulled the US out of the deal, arguing it had failed to curtail Iran’s missile programme. Iran resumed work on its nuclear programme the following year.

Today’s release of the UK-Iranian dual national Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe and the repayment to Iran of some $530m owed for British-built Chieftain tanks, ordered by the republic before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, have to be seen in that context.

However, even if sanctions on Iran are lifted, the IEA believes it could be a while before Iranian crude returns to the market.

The IEA said: “Talks between Tehran and the West to revive the 2015 nuclear deal have hit pause but, if and when a deal is struck, it could take at least another month before sanctions are formally eased.

“At that point, we expect production to ramp up by more than one million barrels per day within six months to reach full capacity of 3.8 million barrels per day.

“Iran would also act swiftly to sell 100 million barrels of oil in floating storage but it would likely take many months to fully off-load the oil (Iranian tankers, for example, would need to be re-certified and insured).”

One other source of extra crude identified by the IEA today is Venezuela, assuming the US were prepared to lift sanctions against the country, but again the agency notes that it would only have a limited impact.

It added: “We believe [Venezuela] could increase production by an additional 200-300,000 barrels per day in three to four months, lifting supply to around one million barrels per day.

“We do not expect that levels above one million barrels per day could be sustained without significant investment and repairs to battered infrastructure and there is no evidence that either is underway.”

In other words, the global oil market is going to be very tight for many months, unless Russia ceases hostilities with Ukraine.

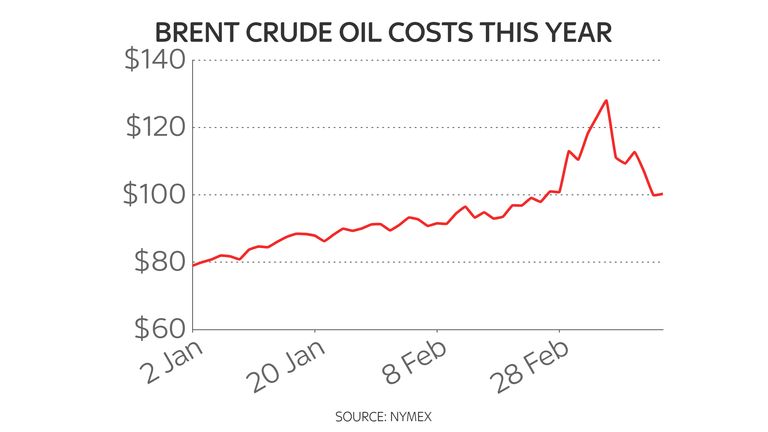

Ms Sen believes the decline in the oil price over recent days, which has seen the price of a barrel of Brent crude fall by almost 30% from the peak of $139.13 it hit on 8 March, is merely due to a lack of liquidity in the market and says it is not inconceivable that crude could hit $150 per barrel in coming weeks.

The good news is that it is starting to become more clear how much of an impact the war in Ukraine will have on the oil price.

The bad news is that oil supply, during the next three months, is likely to be 700,000 barrels a day lower than demand.

Consumers have little choice but to turn down the thermostat, slip on a jumper, use the car less and hope for a warm spring.