Above the Elysee Palace, the sky was big and blue. It could have been a perfect Paris day, except that the topic for debate was pressing, and grim.

As the sun beat down, the president was talking to his senior ministers about how to react to the rapid rise in infections, hospitalisations and admissions to intensive care.

Worried about the impact on the economy and education, Emmanuel Macron has been reluctant to embrace a full lockdown.

His Prime Minister, Jean Castex, has been more open to the idea and so, it seems, have a growing number of French citizens, with polling suggesting a majority in favour of a strict lockdown, akin to that which France experienced a year ago.

In the end, Macron did not go that far, but he did extend restrictions across the whole country. Everyone in France now has to live with a curfew, the closure of non-essential shops and a call to work from home.

Schools will be shut for three or four weeks, although they would have been closed for holidays for some of that time, anyway.

The question is whether Macron has gone too far, or not far enough. He said he had left it as late as he could to bring in these new rules, and patted himself on the back for guiding France away from the sort of recent lockdowns seen in Italy or Germany.

But he said that it was not an option to do nothing, and pointed out that the third wave was having a greater impact on younger people – 44% of the people in France’s intensive care units are under the age of 65.

Macron’s gamble is that these national restrictions will restrain the third wave sufficiently over the next month to allow a loosening at the end of April. But France faces four significant problems.

Firstly – the so-called “British variant” is now the main driver of new cases. Macron referred to it as “an epidemic within an epidemic”.

Secondly – it’s clear to anyone who visits the country, and particularly a big population centre like Paris, that the fear of breaking the rules has ebbed away.

I saw groups of people, their masks wrapped around their necks, standing next to each other in big groups in shopping streets. Where once the curfew meant empty streets, the roads in the middle of the capital are now busy with people driving.

Thirdly – intensive care units are now almost all full. Extra help, including the military and medical students, is being drafted in to help boost capacity. But we are already hearing stories of doctors having to decide which of their critically ill patients is more deserving of treatment.

And fourthly – vaccines. France, like most of Europe, has had a sluggish, stuttering start to its vaccine rollout, hindered by a lack of doses and exacerbated by scepticism among a minority of the population and the president’s unwise choice to raise doubts over the AstraZeneca vaccine.

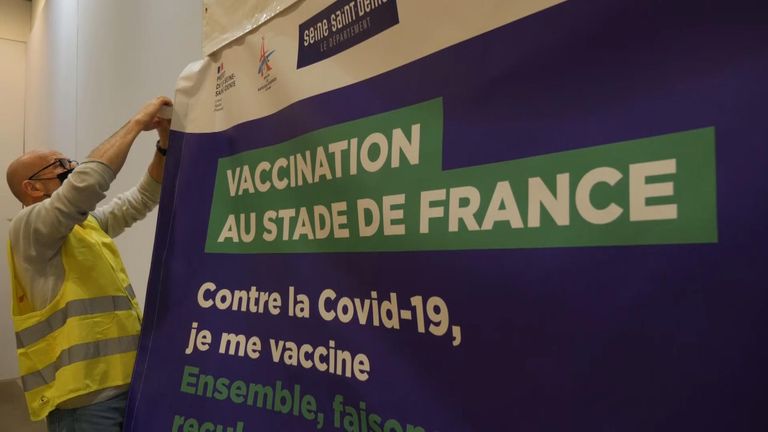

We visited the Stade de France, the national sports stadium, where a vaccination centre is being built. You might imagine it would be huge, with temporary buildings on the pitch and the executive boxes converted into treatment rooms.

Instead, most of the facility is housed in a converted conference room, which won’t be open for a week. Then, it will be able to deliver 10,000 vaccinations per week – good, but not exactly spectacular.

Fundamentally, though, the problem is that, at the moment, France does not have the vaccine doses to satisfy demand.

And sorting that will involve a combination of patience, to wait for new vaccines and new supplies, and political nous in trying to squeeze more supplies out of AstraZeneca.

Outside Paris, we visit Crepy-en-Valois. This small town has the dubious distinction of being the place where France lost its first victim to COVID.

When I came here to film, not long after, it was a ghost town – shut down and eerily quiet.

Now, it feels alive again. A small vaccination centre has been set up and a sign on the reception desk tells me that nearly 5,000 people have been given the jab here.

I walk around with Luc Chapoton, the spokesperson for the town’s council.

Given the choice, he would have preferred a strict lockdown “because that is what people respect, and when we have that then the epidemic declines”.

He shows me the fridge where the vaccines are kept, which empties almost as soon as it fills. They are proud of their ability to make the most of all the supply that is sent – not one dose has been wasted – but Luc says it is always a battle to get more doses sent over.

“We have to fight, he tells me. “We have to fight against others for vaccinations, to prove that we have some patients that are waiting for the vaccines and who need them. Yes it’s a fight. It’s a negotiation, a permanent negotiation.”

As France enters its latest period of restriction, it is an unsure country. The third wave is racing, while the vaccine rollout is meandering. The blend of those two things will define the shape of the coming weeks.